Jenny Hall

Verses from the Dhammapada 404

The simple life may not sound very exciting and 'I' likes stimulation to keep me interested and engaged. However, the attitude we take towards things is key in how we experience them. Jenny Hall explores this connection in this latest verse.

_190523050003.jpg)

“He is a Brahmin, who is content with a simple life.”

In Goethe’s famous poem The Sorcerer’s Apprentice, the apprentice of the title is a lazy boy. His master, the sorcerer, announces that he is going to visit a friend. He gives the apprentice instructions to fill a cauldron full of water from the well during this time, and to sweep the floor and light a fire – but to touch nothing else.

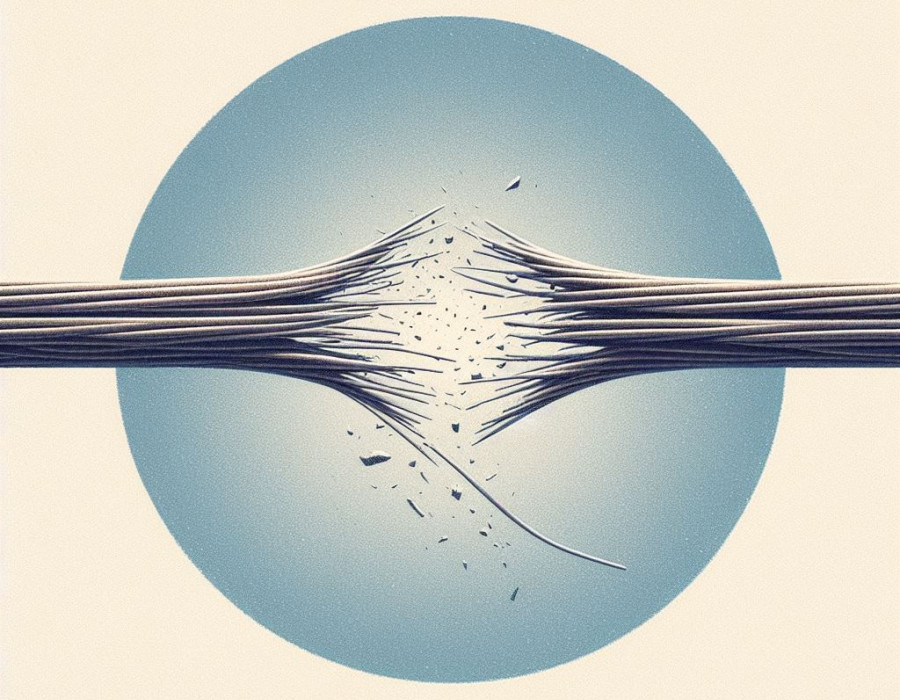

The boy is not only lazy, but also very bored with the mundane tasks with which he is charged. He decides to spend some time looking in the sorcerer’s book of spells. He comes across a spell that animates a broomstick and makes it obey commands. Filled with excitement, the boy casts the spell. Immediately, the broomstick grows arms and legs, walks to the bucket and lowers it into the well. Once the bucket is full, the broomstick tips the water into the cauldron.

The boy is delighted, until he realises that the broomstick is unable to stop. The floors quickly flood with the excess water. In desperation, the boy grabs an axe and chops the broomstick into pieces. Each piece transforms into a new broomstick, complete with arms and legs, and each continues filling the cauldron with more and more water. By now, the water has reached the ceiling. Then the boy hears his master return. In a loud voice, the sorcerer breaks the spell and orders all the water back into the well.

Like the young apprentice, we often become bored with “a simple life”. As the theologian Thomas Traherne remarked, we are drawn by expectation of, and desire for, some great thing. When we embark on the Zen training, some of us may grow disappointed upon hearing our teacher’s instructions to keep a daily timetable and to give ourselves wholeheartedly into whatever activity is being performed.

Daily life practice reveals that, whilst carrying out our chores, we are often on ‘autopilot’ – daydreaming of something we have judged as more interesting. Before replacing our old, familiar gas cooker, telling myself I didn’t enjoy cooking, I would light it carelessly. However, the knobs on the new one were arranged in a different configuration; the method of ignition was also different. Close attention was required to use it safely. My husband gave himself sensibly into the new sequence of movements. I did not bother to do this, and frequently failed to light it. Exasperated, I exclaimed on one occasion: “It doesn’t like me!”

When we give ourselves wholeheartedly into tasks, then the ‘I’ drops off, and the oneness of choiceless awareness opens. There is a mutual helping. ‘I’ lose myself in lighting the oven; the oven is helped in to function according to its design. With ‘me’ out of the way, stirring the porridge is no longer boring. As we give ourselves, over and over, we experience the realisation that every object is helping and supporting us.

Choiceless awareness always reveals the ‘next thing to be done’. We don’t need to think about it. It is shown from moment to moment. In Charles Dickens’s David Copperfield, David has run away to his aunt in Kent, Betsey Trotwood. He is weary, footsore and bedraggled from many days and nights on the road. Betsey, considering David’s future, appeals to her friend Mr Dick: “What shall I do with him?” she asks. Mr Dick sees how dirty David is, and says: “I should wash him.” Later, when Betsey’s mind drifts to the future again, she asks: “What would you do with him …?” Mr Dick, seeing how exhausted David is, says: “I should put him to bed.”

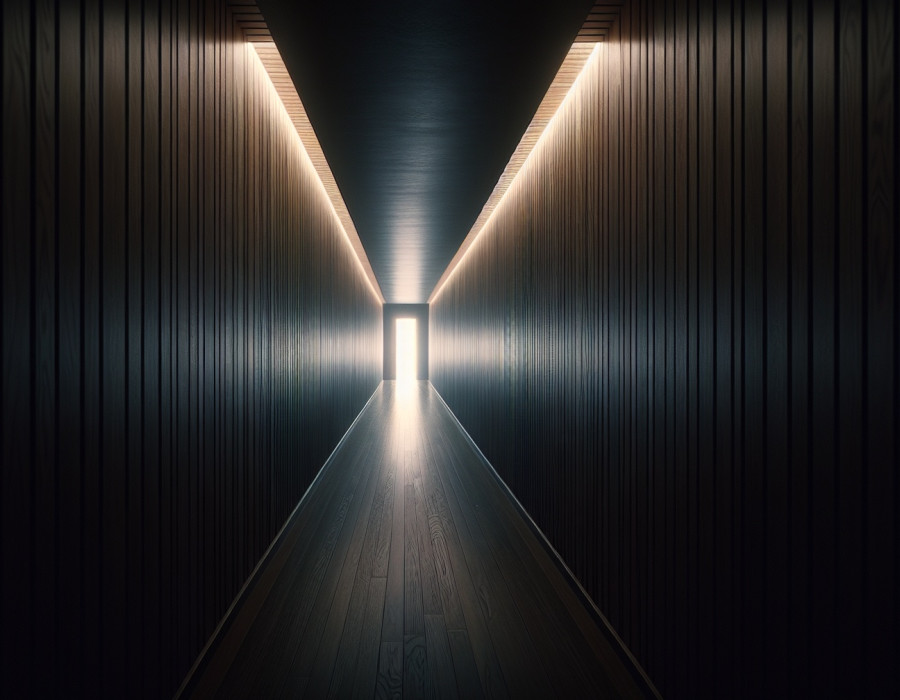

Choiceless awareness, free from ‘I’, always acts appropriately, for the good of all. As we give ourselves into getting out of bed and opening the bedroom door, choiceless awareness performs these actions quietly; our sleeping partner is not disturbed. Quiet walking across the floor doesn’t alarm our neighbour below. We give ourselves into cleaning away any scum around the bath, readying it for our partner to use. The towel is carefully hung up to dry. So the day continues. When we give ourselves in this way, we are ‘one’ with each changing situation. This is what the Heart longs for. This is ‘a simple life’.

At eighty years old, Master Hyakujo continued to work in the garden, giving himself into trimming, cleaning and pruning. His pupils believed he worked too hard; they decided to hide his tools in order to give him a rest. Hyakujo then ceased eating. Upon seeing this, the pupils put the tools back. Hyakujo then worked – and ate – as before. In the evening, he said: “A day without work is a day without food.”

In choiceless awareness, there is joy in what Thich Nhat Hanh calls “household delights”. Jean-François Millet’s beautiful painting The Angelus depicts a farmer who has been digging potatoes, and his wife, who has been loading them onto a cart. They bow their heads reverently in the gathering dusk, expressing their quiet gratitude.

© Jenny Hall