Jenny Hall

Dhammapada Verse 87

Verses from The Dhammapada

The Buddha taught that the very nature of life involves uncertainty and the suffering that this causes, but also that there is a way out.

©

© shutterstock

“Leaving the way of darkness, the wise man will follow the way of light, leave security behind and seek freedom from attachment.”

This verse refers to the fourth of the Four Great Vows of the Bodhisattva: “The Buddha’s Way is supreme; I vow to walk it to the end.”

When a new year begins, as we watch reviews of the old year on television, we might be filled with trepidation. Endless images of strife are paraded before us: wars, natural disasters, acts of terrorism. These events reflect the conflict in our own hearts; we may wonder what the future holds for us. Perhaps we make plans in the hope of securing it.

“Leaving the way of darkness …”

At each stage of life, we embark on various means to this security. We may obtain a new qualification or job, a new partner or home, or undertake new hobbies. Yet the heart still whispers the question: Is this all? As the years pass, our qualification becomes outdated, and we may be made redundant; our feelings for the relationship may become stale; we become bored with our hobby.

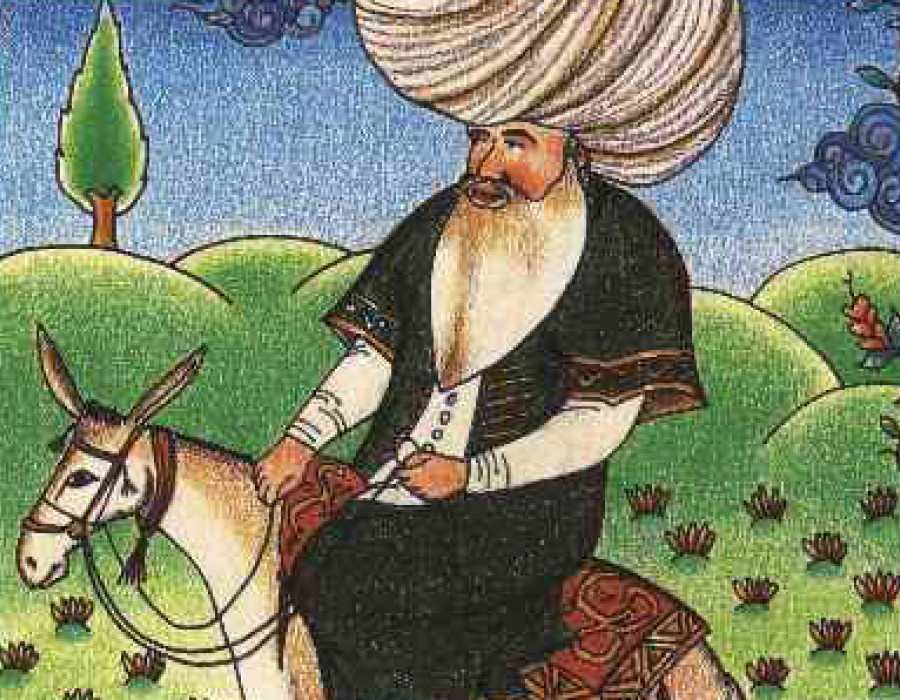

The Sanskrit term samsara expresses our confused behaviour. It means ‘wandering around’. We are never satisfied. We constantly believe that security and fulfilment could be obtained by doing something else, being somewhere else, having something else or being with someone else. As we grow older, we may yearn for early retirement; however, when it arrives, this, too, doesn’t quite supply the answer, either. We become bored and restless, with old age and poor health dominating our outlook – and finally, we have only death to look forward to.

The Buddha taught that the very nature of life involves both uncertainty and unease. He taught that the First Sign of Being is impermanence. The Second Sign is suffering. He explained that suffering arises when we attempt to resist change, either by clinging to or resisting what was or what is. Driven by desire and hate, we make judgements and attempt to bring about what pleases ‘me’. We are goal-orientated.

A neighbour was recently taken into a care home. Before her house could be cleared out, all current financial documents had to be found and sorted for the solicitor. Any out-of-date papers needed to be collected and made ready for shredding. Over many years, both old and new papers had been stored around the house in dozens and dozens of shoeboxes and carrier bags. No sooner had one bundle been sorted than another was discovered. After many hours of work, I believed that the task was complete. I relished the thought that now I could go home and relax with a book I was looking forward to reading. Yet something compelled me to look under the bed: there was a large suitcase there, stuffed with still more papers.

We may embark on Zen training in the same way, regarding enlightenment as the ‘goal’ at the end of the path. We strive to achieve it, believing it will lead to security – something for ‘me’. The Buddha taught that such images need to be let go. In fact, these images actually make up ‘me’. The Third Sign of Being is ‘No I’; the Buddha taught that the ‘I’ is a delusion at the root of all our problems, fears and insecurities. This delusion constantly seeks to bolster itself through permanent comfort and pleasure, which endlessly elude it.

‘… the wise man will follow the way of light.’

In Zen training, we learn to be present in each moment. There is no ‘goal’. The path itself is the destination. We are not looking for a place of peace and security for ‘me’. In fact, we are encouraged to recognise the uncomfortable feelings that drive us.

In the Greek myth of Theseus, the Minotaur – half-man, half-bull – lives in a labyrinth made up of many confusing paths, rather like the ones we follow in search of fulfilment. The Minotaur can be seen as a symbol of the heat and strength of desire and hate. Theseus listens carefully to its breathing and finds his way into the heart of the labyrinth, where the Minotaur lives, in the same way that Zen training teaches us to meet and greet our churning and burning passions. When we are burned away, an inner space opens.

When we give ourselves wholeheartedly and repeatedly away into the energy or ‘fires’ of passion, into what, at this moment, is being done, then there is no ‘I’ left to keep judging ourselves or others. I am no longer a slave to whether something interests or bores me. There is no ‘I’ looking for a result. There is no desire to ‘get’ a task ‘out of the way’, because ‘I’ am out of the way. There is no ‘I’ to regret the past or dread the future.

William Holman Hunt’s painting The Light of the World symbolises this ‘way of light’. The figure of Christ, wearing a crown of thorns and holding a shining lantern, knocks on a door. The crown of thorns points to suffering met; the door symbolises ‘me’, the barrier to ‘reality’. When ‘I’ am given away, the door opens.

The lantern is the light of consciousness: empty space, also called ‘choiceless awareness’, which sees things as they really are. It shines in warmth and joy, at one with all.

What is there to fear?

© Jenny Hall