Jenny Hall

Verses from the Dhammapada 250

Jenny Hall explains how 'I' use thoughts about past and future to grasp and how this prevents us resting in the 'now'. In this way we find it difficult to accept this moment as 'enough'.

“He who is not greedy has peace of mind by day and night.”

Greed very often drives the thoughts that create the idea of ‘I’. At the start of the New Year, our thoughts tend to turn to the one gone by, and to the future. Such mental activity makes up psychological time, which is interchangeable with ‘I’.

“He who is not greedy …”

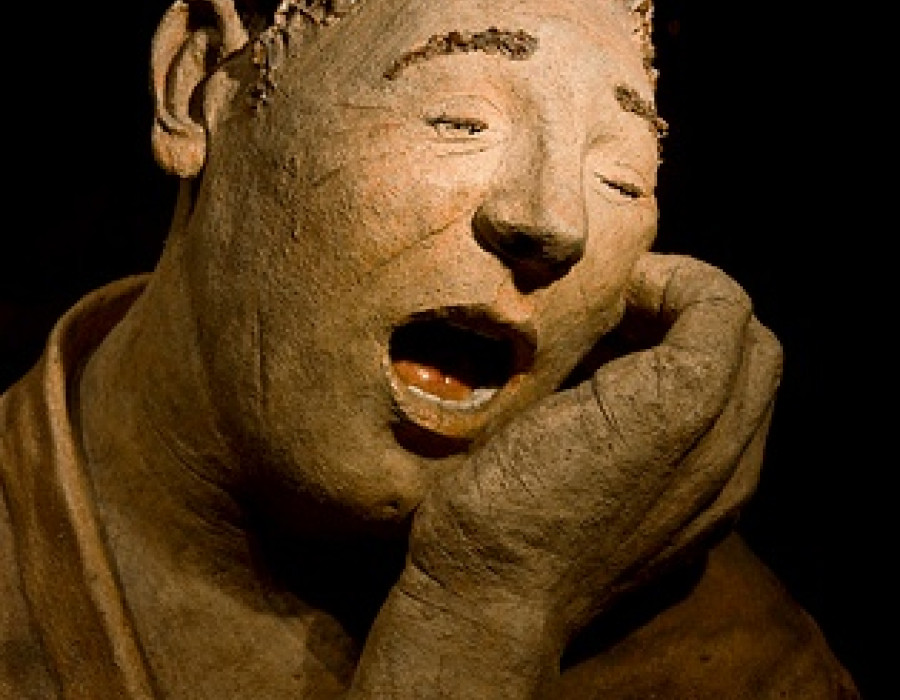

It is the nature of ‘I’ to be greedy. ‘I’ am never satisfied. When I have judged something as pleasing to ‘me’, I cling tenaciously to it – and want more.

A king lived in a magnificent castle, set in a beautiful garden. Although he possessed everything money could buy, he was never satisfied. In the forest bordering his garden lived a nightingale. When the king was feeling particularly unhappy, he would take a walk in this forest. Very rarely would he catch a glimpse of the nightingale’s plumage, but its cheerful song would lift his spirits momentarily.

One day, the king decided that if he could only catch the nightingale and keep it in the castle, he would be content forever. He sent his huntsmen into the forest. They searched high and low for the bird, but were unable to find it. The king was furious. He commanded his craftsmen to design and manufacture a mechanical bird encrusted with glittering precious jewels. When the bird was wound up, it flapped its wings and sang. Its song was similar to that of the wild nightingale.

For a while, this mechanical nightingale lifted the king’s mood. However, through constant use, it began to wear out. In order to protect its internal mechanisms, it could only be wound up once a year.

Gradually, the king forgot about it. Years passed, during which he fell into a deep depression. Nothing gave him pleasure. He took to his bed, and refused to eat or drink. Seeing that the king was about to die, his manservant called for the mechanical bird. He tried to turn the key, but it had rusted from disuse. The mechanisms had completely worn out.

Suddenly, the joyful song of the wild nightingale could be heard. The servant flung open the window. In a flash, the nightingale flew into the king’s bedroom. The king sat up immediately and smiled. He pleaded with the bird to stay.

The nightingale replied: “I cannot build my nest in the castle. Let me visit whenever I want to.”

In this story, the king is ignorant of the Buddha’s teaching that craving and attachment create suffering. Everything, after all, is in a constant state of flux. As Emily Dickinson writes, in one of her poems: “[That] it will never come again.”

The king attempted to possess the ephemeral, wild nightingale by capturing it. The mechanical bird symbolises his effort to make it permanent. Why did he yearn for the bird? When he first heard it, the sound – just for a moment – extinguished all self-consciousness. It was this freedom from ‘I’ that the heart longed for, not the bird itself. Zen training encourages us to meet the hot flames of greed and invite them to burn ‘me’ away. Then the heart is fulfilled.

‘… has peace of mind by day and night.’

The idea of yesterday and tomorrow create the idea of ‘me’. When visiting a friend, I noticed an unusual bird pecking at her bird feeder. For a split second, the unexpected sight stilled all thought. There was no ‘me’. There was no consciousness of time. Then I returned to the past, and said: “I saw one of these in our close only yesterday.” I added: “I think it’s a Great Spotted Woodpecker. I’ll look it up in my bird book when I get home.” In this way, the image was then carried into the future. Psychological time and ‘I’ are one and the same: ‘I’ am made of memories. ‘what I’ve done what has happened to me and what I hope will happen. Zen training encourages us to give ourselves wholeheartedly into whatever is being done. In this way, thoughts of yesterday and tomorrow are constantly emptied out. When ‘I’ am out of the way, time disappears. Then there is no day and night. This is peace.

Perhaps we believe we can work toward world peace in the future through ideology or revolution. The future, however, never comes. We must find peace now by giving ourselves to every moment, as expressed in the following story:

Tenno had recently become a teacher of Zen. He decided to visit Master Nan-in, who greeted him with a bow. He then asked Tenno: “I expect you left your clogs in the vestibule. Did you leave your umbrella to the right or left side of your clogs?” Unable to answer, Tenno realised he was still not giving himself wholeheartedly to every action in every moment. He gave up teaching and became Maser Nan-in’s pupil for another six years.

Through ‘every-minute Zen’, we can live in the peace of the timeless.

© Jenny Hall