Jenny Hall

Verses from The Dhammapada 1

If the space in between thoughts can be opened up to, the transcendental can appear.

Rodin's The Thinking Man statue

By Erik Drost, CC BY 2.0 <https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0>, via Wikimedia Commons

‘All that we are is the result of what we have thought: it is founded on our thoughts and made up of our thoughts’.

This verse points to the constant thought streams which create the mistaken impression that ‘I’ am a permanent entity.

When we keep thinking about something it can easily become a preoccupation. This preoccupation gives rise to even more thoughts. It’s not long before we are in the grip of an obsession. During the ‘Should we Brexit or Remain?’ dispute, it was difficult not to be drawn in. There was endless coverage in the media and on-line. Soon many were avidly following the debate. Although it was impossible to be in possession of all the facts, opinion rapidly polarised. Families and friends were soon divided. Rancour flared as each side built itself up by ardently defending its viewpoint. In such way thought reinforces the idea of ‘me’ and creates and then denigrates ‘others’.

The Zen training shows us how to free ourselves from these delusions. In zazen we give ourselves wholeheartedly into counting the breath, one to ten. When the count is lost through thoughts, we bring ourselves back to it. At the beginning we may feel frustrated. Perhaps we can’t get beyond 1…, 2…., 3…., before thoughts start crowding in again. We may begin to feel that we are engaged in a battle with them.

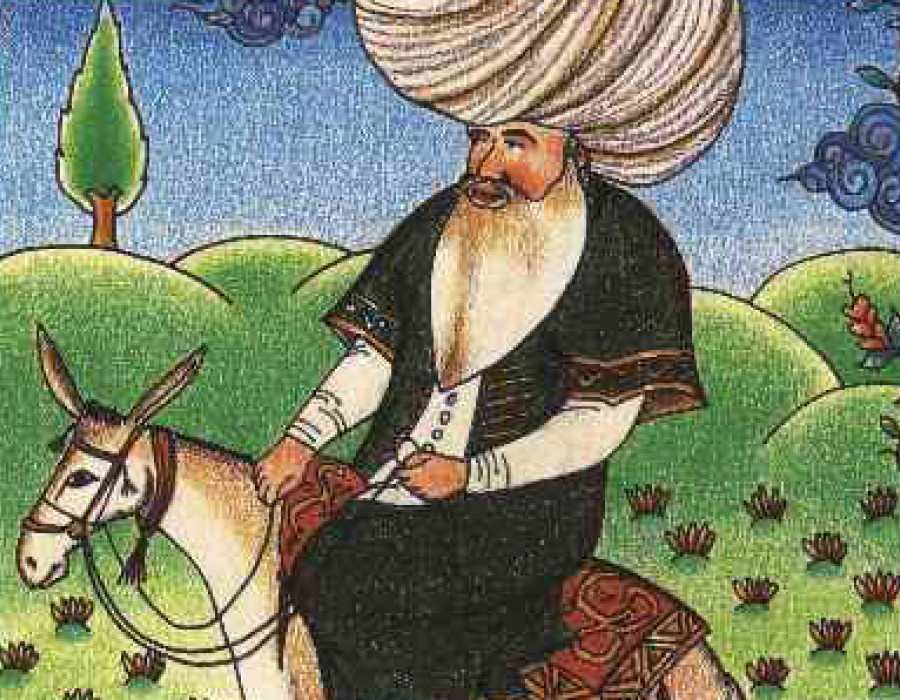

There is a story about a Sufi mystic called Hussain. He was staying with a wise woman called Rabiya. Five times a day Hussain prayed for spiritual enlightenment. He kept repeating ‘I am knocking, Sir, why hasn’t the door opened? I’m beating my head against your door, Sir. Open it!’ Rabiya listened to this prayer for three days. Then she said, “Hussain, you are too concerned with your thoughts. You are talking nonsense. All this talking and shouting is closing your eyes. Why don’t you just look. The door is already open.’

However, it is the nature of the mind to think. Ajahn Chah once said, “Our thinking doesn’t have to stop.” All we have to do is to notice when it has arisen, and then come back to counting the breath. The breath is always there. We can relax. It is not necessary to pay much attention to the thoughts. We don\t have to feel we have to stop them. They will naturally quieten. Awareness of the space between them will open. Then there will be no ‘I’ to name it.

Every moment of the daily life practice offers the opportunity to abandon self- consciousness. Our teachers advise us to give ourselves wholeheartedly into whatever is occurring.

A few years ago, I was tackling a pile of ironing (a task I had told myself I disliked). A letter to my teacher was due. As I half- heartedly dabbed at a T-shirt with the iron, I wondered what to write in the letter. Suddenly an image of my teacher demonstrating how to give ourselves into the ironing popped into my head.

There was a wholehearted pressing the T-shirt. All thoughts of ‘me’ and ‘the letter’ disappeared. There was just the ironing.

When we embark on an activity which we have judged as enjoyable, we give ourselves easily and therefore ‘choiceless awareness’ opens up. In Autumn, such a task is sweeping up the leaves in the Close. Last year, the task had to be abandoned because of a chest infection. As the leaves began to fall and pile up, thoughts arose concerning the neighbours.

“Why can’t someone else take responsibility for clearing up the leaves? How untidy the Close looks!”

After a few days, it was realised that this was a training opportunity. The annoyance was met and allowed to churn. In this way the emotional energy, instead of being wasted in thoughts, was conserved. Choiceless awareness opened. Looking out of the window it was noticed that the wind had swept the leaves into beautiful patterns which glowed with warm colour. Not long afterwards a newly arrived neighbour and her two children spend a whole morning sweeping and bagging the leaves. Joy and gratitude arose and was communicated to them.

When a monk asked Master Joshu “What is the meaning of Zen?” He replied “The oak tree in the garden.” This was choiceless awareness speaking. It wasn’t an answer that Master Joshu thought about. It wasn’t intended to be remembered for another occasion. It was pointing to the ‘thusness’ of things in each changing moment.

Zen Master Hung Chin said:

“Silently and serenely one forgets all words,

Clearly and vividly THAT appears before him.

When one realises it,

It is vast, without edges.

In its essence one is clearly aware.”