Jenny Hall

Verses from the Dhammapada 129

When we want something to change, we may try to to get rid of, ignore or even destroy obstacles in our way. The Buddha taught however, that this will only cause us more suffering.

''All tremble at the pain of the rod, all fear death. Comparing others to oneself, one should not strike or kill.”

As a child, I witnessed a little boy in hospital screaming as he was being given an injection. I was haunted by this image for many years, and became terrified of syringes. In my early twenties, it was necessary to have a course of injections in my legs. So great was my aversion that, on each occasion, I fainted.

In the Pali Canon, we find the story of Siddhartha and the swan. Nine-year-old Siddhartha watches as a swan, shot by an arrow, drops from the sky and writhes in agony. He goes immediately to the swan’s aid, pulls out the arrow and takes the bird into his arms. He is about to carry it to the palace when his cousin Devadatta runs toward him, shouting, “Give me the bird! I shot it – it’s mine!”

Siddhartha replies: “Those who love each other, live together. Only enemies live apart. You tried to kill the swan. You are her enemy. The bird needs my care and protection.”

The wounded swan can be seen as a symbol of pain. Like Devadatta, we usually attempt to ‘kill’ it. We pass out, or take a painkiller, or attempt to distract ourselves. At some point in our lives, however, it becomes impossible to escape pain; Siddhartha’s tender care of the swan points to the importance of embracing it. As the Buddha, he taught that such acceptance leads to the discovery of Buddha Nature – that is, the strength and resilience that are beyond ‘me’.

A monk once asked Master Rinzai where his teaching style came from. Master Rinzai replied that when he was training under Master Obaku, he asked him three questions. Each time, Master Obaku beat him. The monk, upon hearing this, was unsure how to respond, and hesitated. Rinzai then hit him, saying: “One cannot drive a nail into empty space.”

To Western sensibilities, such stories may appear rather shocking. We tend to judge such actions reflexively as ‘cruel’. However, they stem from deep compassion. They are a means of awakening the pupil form the dream of ‘I’, in the same way people often slap a hysterical person in order to help bring them back to their senses.

All Zen training is in the body. The choiceless awareness that arises through samadhi cannot be taught through words, which, in fact, constitute a barrier that obscures it. Venerable Myokyo-ni would present us with opportunities to share this insight. She would instruct us to pinch our own arms. Ouch! In the act of pinching, there is just the sensation; although we can think about the pinch, no thought can approach the sensation. In that bare sensation, there is no ‘I’ to suffer or complain.

When sitting zazen at first, pain would invariably arise in my knees. I knew that moving wasn’t an option; part of the daily routine involves sitting zazen for a specific period of time. At first, aversion to the pain arose. How much longer do I have to put up with this? It’s unbearable! However, resistance disappeared when I gave myself wholeheartedly into the count, and choiceless awareness opened up. It was always in touch with the pain, but there was no ‘I’ to react – just a bundle of sensations, moving and changing, coming and going. Choiceless awareness allows these sensations simply to be. It was just pain; sometimes it faded altogether.

In the early stages of the training, we may be tempted to adjust our postures to relieve the pain. We often do this in life, too. Perhaps we slump, for example. Over time, such habits actually place more stress on the body, and we may even seek physiotherapy to redress the imbalance.

My long-held fear of syringes and needles in general has now disappeared. Recently, giving myself wholeheartedly to a course of acupuncture treatment, the needles produced only a set of changing sensations. Although it lasted thirty minutes, I felt no fear or resistance.

When fear has transformed into the strength and compassion of choiceless awareness, this transformation naturally benefits all. When a friend is suffering, we can sit and meet the pain together.

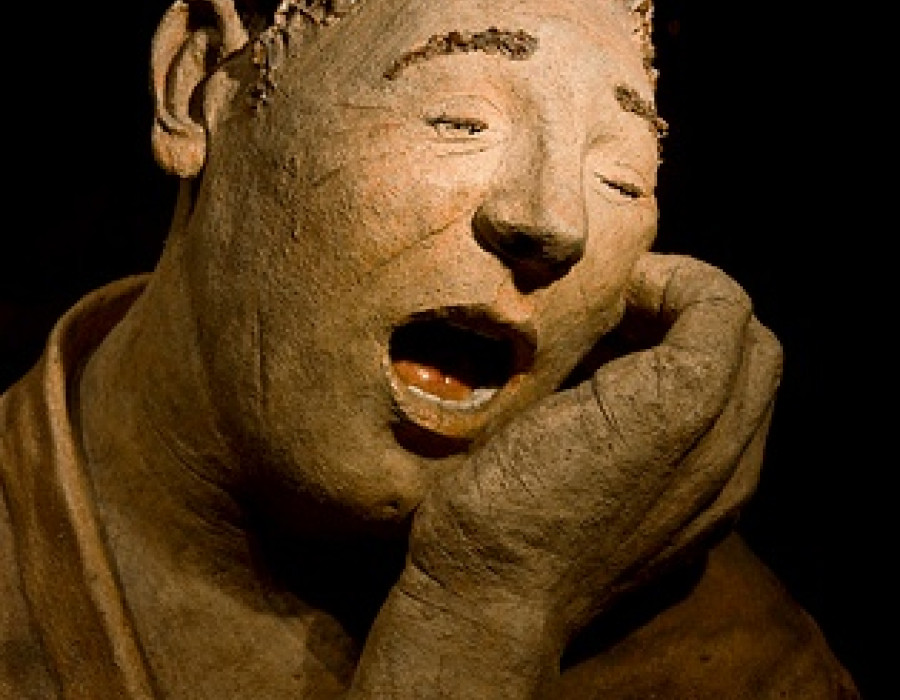

Fra Angelico’s mysterious picture The Mocking of Christ, in which Christ is tormented whilst in the presence of the Virgin and Saint Dominic, points to just such a sharing. Christ is blindfolded, symbolising an inner looking, a meeting of the pain. He is assaulted by slapping hands and a stick, while a man to his right spits at him. The Virgin and Saint Dominic sit by, calmly. Christ holds the sceptre and orb – emblems of triumph over suffering.

Pema Chödrön has said: “When we sit with discomfort without trying to fix it, when we stay present [with] the pain [and] let it soften us, these are the times we connect with bodhicitta [the aspiration to Enlightenment said to be a natural function of the human heart].”

© Jenny Hall