Dragon-Slaying: A Policy for Disaster (part II)

Blog

Is it is good to annihilate evil? The Buddha's teachings on dependent origination show us how 'slaying dragons' may have grave consequences for the future.

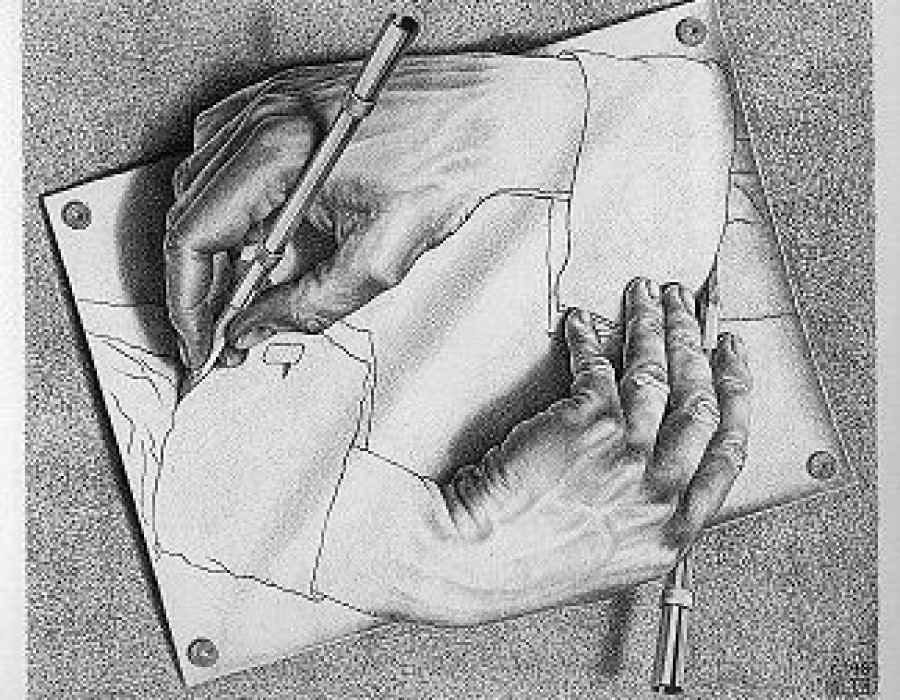

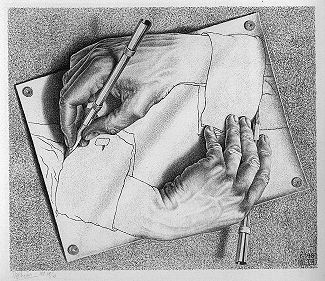

Drawing Hands by M. C. Escher

Fair use, https://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?curid=3475111

Joseph Campbell was a leading figure in the field of comparative mythology. Editor and friend of the Swiss psychologist Carl Gustav Jung, Campbell was a great believer in the power and importance of myths. Like Jung, he believed that myths contained the basic ideas that provide the structure for our thought and consequent behaviour. Another term for these basic ideas is archetypes. Jung popularised the notion of a collective psyche (Greek: soul) populated by archetypal forms and proposed that these forms could be found underlying whole cultures. Campbell spent a lifetime exploring Jung’s hypothesis through his close examination of the myths that gave birth to the world’s different cultures.

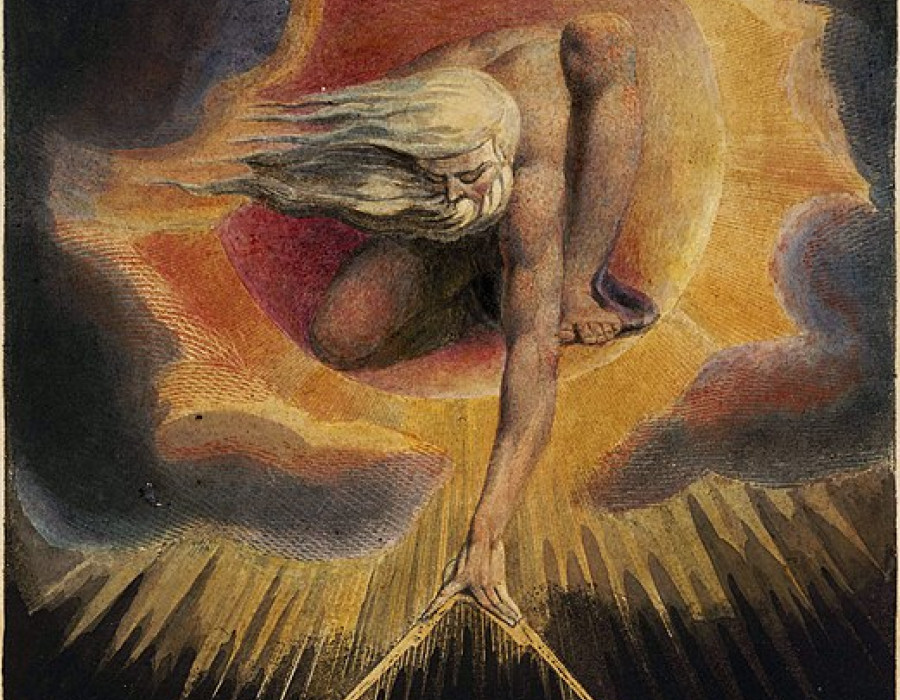

Campbell identified the dragon slayer as one of the central figures in Western mythology. St. George and the Dragon, a founding myth of the British Isles, is a prime example of a dragon slayer story. The relevant point here is that even though we made the transition from a medieval Christian society to a modern secular one, the underlying way we think still permeates our new beliefs and ethical values. For example, there’s the archetypal idea of the apocalypse: a terrific struggle between good and evil that culminates in a final triumph for good. This idea exists in both Jewish and Christian belief systems, but can also be found in political ideologies. In Marxism, the evil of capitalism will, through historical necessity, be vanquished by the good of a communist world society. This way of thinking exists in any ideology that has a set goal: racial justice, eliminating carbon emissions, achieving Brexit, or even getting rid of Donald Trump. This is the nub of the dragon-slaying myth: the hero represents the ‘good’, the dragon the ‘evil’. The hero slays the dragon; evil is vanquished and good prevails. This way of thinking also permeates what could be called the ‘myth of progress’, which is probably the most powerful myth of our time. It posits that we start in ignorance and progress bit-by-bit toward a supremely positive end, after which there is presumably an eternal heavenly state.

The myth of progress notwithstanding, things seldom work out as we imagine. The attainment of good is slippery and elusive and keeps getting pushed into the future. Just as our goal appears on the horizon something emerges to thwart it. Yet it’s very difficult for us to challenge the underlying truth that eventually ‘good’ must triumph over ‘evil’ because it’s the basic assumption we’re working from. Such an assumption is what the Germans call Weltanschauung or world view. At best it’s only semi-conscious, so instead of dropping a world view when it doesn’t pan out, we adjust it by adding a new belief. In the case of the dragon-slaying myth that additional belief is centred around the notion of a scapegoat.

The Book of Leviticus in the Hebrew bible recounts the ritual of the scapegoat. In ancient Israel two goats would be selected for one of the most important rites of the year. One goat was offered to God at the Temple in Jerusalem. The other was ritually given all the sins of the people and driven out into the wilderness. Possibly the goat was thrown over a precipice as a sacrifice to a fallen angel who represented the presence of evil on earth.

In psychology the scapegoat represents everything that opposes the attainment of a goal. The scapegoat is there to fix the bug. If progress is the natural state of affairs, obstacles are not a feature of this progress but simply things to be fixed and removed. This means that progress will have to be continually managed until the goal can be attained. The myth of progress demands that there’s always something to be done. The bugs need to be fixed. They must be managed either by you and me or by experts and governments. But what if this doesn’t reflect the nature of things as they really are? What if the myth of progress and the need to remove scapegoats is only a partial truth or incomplete myth?

The Buddha’s parable of the blind men and the elephant is a good illustration of a partial truth. Each blind man touches the part of an elephant closest to him and declares that the whole elephant resembles a fan (ear), a column (leg), or is round (belly) or snake-like (trunk) etc. Of course, each blind man is convinced that his own interpretation is the whole story whereas in truth it’s only partially true and therefore incomplete.

Myths, residing mostly at the unconscious level, contain powerful emotional energy. As a result, they tend to be readily accepted as universal truths. Ideologies draw upon the same unconscious power as myths. Freud’s psychoanalytic theories were also presented as universal truths. He reduced religion, art and all human behaviour to components in his map of the human psyche. These ranged from the id’s sublimation of impulses to the decrees of the superego. Marx on the other hand presented his universal truths through the lens of the class struggle. Critical race theory, a modern day off-shoot of Marx’s theory of class warfare, presents its own insights through the lens of the oppressor and the oppressed. When all human activities - from the arts and sciences to the underlying structure of thinking - are seen through the lens of a universal category even the notion of inclusivity can exclude other ways of seeing. Universal categories can help us understand the world and our place within it, but a serious problem arises when they exclude all other ways of seeing and leave us with only one way to see the world. The inevitable result of any narrow vision of the world is extremism and violence. This is why the Buddha proposed a Middle Way.

Yin Yang

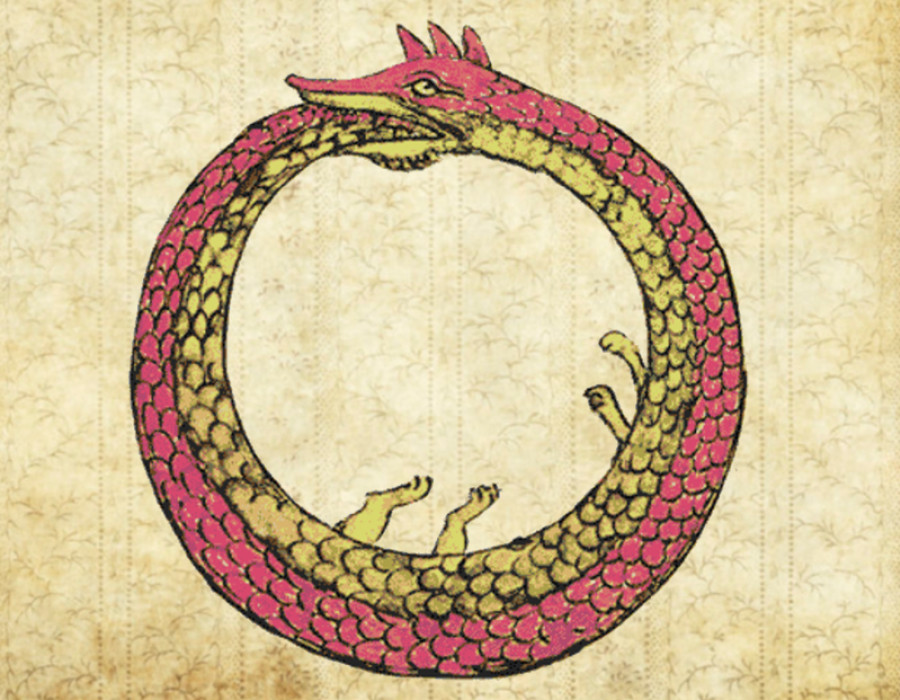

Joseph Campbell contrasted the West’s dragon-slaying myth with the Chinese Yin-Yang symbol. Here an unbroken circle is divided in two to create the shapes of a black fish with a white eye and a white fish with a black eye. The tail of the black fish grows until it reaches a maximum width at which point the seed or white eye appears. When the black fish disappears it’s replaced by the tail of the white fish which now increases to a maximum width at which point the seed of the black fish appears. One is then back on the tail of the black fish. This Taoist image was long ago co-opted by Mahayana Buddhism, being especially useful for the teachings of the interdependence and interpenetration of all phenomena

The interdependence of things is clearly described in the Flower Garland Sutra (Japanese: Avatamsaka). Opposites are dependent on each other for their existence. Good arises from evil and evil arises from good. Consequently dragon-slaying cannot eliminate evil so that only good prevails. Continual progress, like continual growth, is simply not possible. Phenomena, or ‘the ten-thousand things’ to use the Chinese phrase, are subject to cyclical arising and passing away. They arise again when the necessary conditions are in place. There is no bug that causes decline and fall so there is no need to find a scapegoat or to eliminate a particular obstacle because obstacles are natural features of the world.

In Buddhist philosophy the world cannot be driven relentlessly in a single direction forever. There is no eternal goal to be attained. Prince Gautama’s father, King Suddhodana, tried to manage the direction of his son’s life by trapping him in the family palace. The prince was protected from the cruelties of life, and carefully prevented from seeing the suffering that surrounded him. Yet this didn’t achieve the goal that his father intended. When the young prince finally came across real suffering it traumatised him, turning his life upside down. In fact it sent him straight down the path of religious life, the very outcome the king was trying to avoid. The desire to make the young prince into a king became the very instrument that set his son on the path to Buddhahood. This is called the wisdom of interdependent origination, the Buddha’s most profound teaching and the one he equated with seeing into the true nature of the Dharma itself. We have to ask ourselves what our problems would look like if the Buddha’s teachings became our habitual way of seeing.

Buddhism has only recently come to the West. Where the Dharma is concerned, we’re still taking baby steps toward penetrating its depths. This is an on-going process and dialogue that will take many generations, but it’s important that we begin this conversation now. Our situation is urgent. Many of us are no longer able to relate to the world that our dominant myths have helped to create.

Buddhism brings 2,500 years of tradition with it, so it’s unlikely that we will be able to simply bolt it onto Western culture. This wasn’t the way it worked when Buddhism traveled from one culture to another in the past. Instead, it developed organically. It arose because of a willingness on the part of its followers to practice hard and immerse themselves in the Buddha’s teachings until they took root and sprouted in a way that was suitable to the new environment.

I mentioned the need for an on-going dialogue. This implies that we need to create venues where we can gather and have helpful conversations, backed up by genuine Buddhist practice. The Zen Gateway was founded in 2012 and since then our mission has been to provide information and resources for individuals as well as groups who want to train in Zen Buddhism. Now we’re about to expand our services by launching a new online community with meditation practice, online courses and dharma talks, and face-to-face meetings with a teacher. Following our survey of newsletter subscribers last year, we discovered that half of those who responded have no regular temple or Dharma centre to visit and rely on material that they find online. We hope that if you have been following us for a while you’ve noticed that the regular contributors to the Zen Gateway all come from a bona fide Zen tradition. Our community will be a place for interaction and dialogue so it’s important to be confident that the teaching you’re receiving is genuine and arises from a living Buddhist practice. At the heart of our tradition is the bodhisattva vow to be of service to all beings. This service arises naturally out of the bodhisattva’s own practice and is based on the principles of interdependence and interpenetration already described. These principles are informed by our daily activities as they are expressed by body, speech and mind. They’re predicated on clarity of seeing and warmth of heart.

The bodhisattva vow doesn’t involve a plan or a management strategy because ultimately we have faith in the power of the Dharma. The power that informs is traditionally called the Wisdom-Gone-Beyond, and it’s a power that we all share and in which we all play a part. Where this leads is not finally up to us. The critical decision for us is whether we’re willing to play our part wholeheartedly in whatever way we can.

If you would like to be kept informed of the Zen Gateway community activities as and when they become available, please sign up to the newsletter on our homepage. This way you can stay in touch. I hope you’ll join us as we take this next important step on our journey.

The Zen Gateway Blog

Dharma, Culture, Philosophy & Life-ways