The Round Table of King Arthur

Our spiritual and moral values arise from ancestral influences. The process of adaptation develops wisdom that is recognised and eventually codified as moral strength. Our traditions and legends preserve this wisdom to be handed down for posterity.

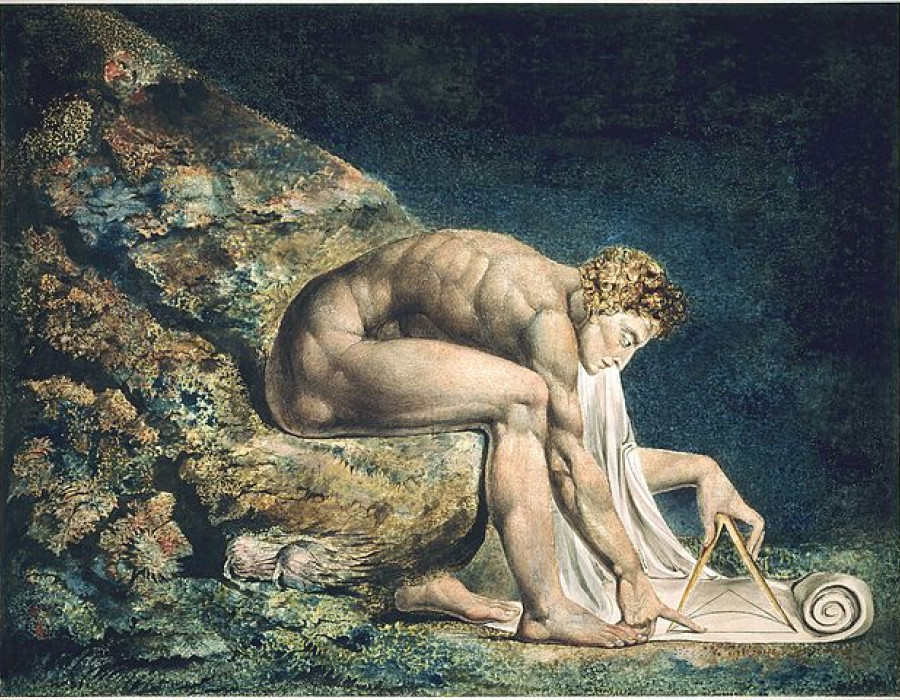

A reproduction of Holy-grail-round-table-ms-fr-112-3-f5r-1470-detail.

[I]n Arthurian legend, the table of Arthur, Britain’s legendary king, which was first mentioned in Wace of Jersey’s Roman de Brut (1155). This told of King Arthur’s having a round table made so that none of his barons, when seated at it, could claim precedence over the others. The literary importance of the Round Table, especially in romances of the 13th century and afterward, lies in the fact that it served to provide the knights of Arthur’s court with a name and a collective personality. The fellowship of the Round Table, in fact, became comparable to, and in many respects the prototype of, the many great orders of chivalry that were founded in Europe during the later Middle Ages. By the late 15th century, when Sir Thomas Malory wrote his Le Morte D’Arthur, the notion of chivalry was inseparable from that of a great military brotherhood established in the household of some great prince.

Encyclopaedia Britannica, online edition

In the primeval forests, long before the first human footprint would appear, the great saurians roamed. Imagine one of these creatures moving through the trees, hunting. Moving through a forested landscape, visibility is low. Creepers hang from the boughs of trees. The vista has no horizon. The creature comes to a clearing. At that very moment, breaking through the undergrowth from the far side, another great beast appears, advancing at full tilt. They almost bump heads. In such a situation, the first rule of the forest is to run in the other direction, if at all possible. However, if turning to flee means exposing a vulnerable flank to a predator’s teeth and claws, then the second rule applies: the one who strikes first will probably walk away from the encounter.

These rules applied throughout the forest as much to our own ancestors as they did to the great saurians.; The impulses that allowed early humans to stay alive are buried deep within us. Our later ancestors discovered that our ability to survive improved greatly if we banded together and cooperated. This strategy required a whole new set of skills and attitudes. In groups, there are hierarchies and rules – spoken and unspoken – that must be obeyed by their members in order for all to survive and thrive. Humans have taken full advantage of this way of life, and of increased intelligence, which social skills demand. We have covered the planet; all habitats are open to us.

But the past cannot be forgotten.

When we become upset by real or imagined wrongs, something ancient surges into consciousness and takes us over. I say or do things that I later regret: “I don’t know what came over me” and “I was beside myself” are just two of the well-known excuses we make for such moments.

The stronger the tendency to diverge from the collective rules, the more severe the sanctions. Viking berserkers used these primordial powers for their battle-craft. Not only were they effective, they were greatly feared. But such an edge comes at a price: they developed hair-trigger tempers that made them less able to integrate into the rest of society, and had to live apart under severe martial law. (Even today regular members of the armed forces are governed by strict rules because of their access to weapons and training, which provide them with lethal skills.)

With time, a new impulse seemed to form, which sought to make a virtue of self-control instead of always relying on ‘outside’ rules and institutions, and reward-and-punishment. The word virtue originally meant ‘power’ or ‘strength’ (hence ‘by virtue of …’). This strength is an inner one, able to contain strong impulses. It became apparent that such virtue could be trained in to a very high level, so that even impulses for self-preservation could be overcome. Thus the idea of ‘noble sacrifice’ for the benefit of a group or community was born. Those who possessed this virtue were ‘heroic’, and gained a sort of immortality that outlasted physical death.

At some point, this virtue became spiritualised, and valued for its own sake. Egalitarian in nature – because it valorises the individual’s personal power over status – it nevertheless remains in a relationship with hierarchy, which is seen as a fomenting influence. The rules of the Buddhist sangha, and of the arhat or bodhisattva (who are free to keep or break the rules because their conduct is motivated by the welfare of the group rather than their own self-interests) are a case in point.

This is the ideal, at least, and thus a spiritual principle – one to which the heart aspires. That it may not always be attained means that ‘earthly’ authority, the authority of the group, is still a requirement. In the Western medieval period, the notion of ‘chivalry’ caught the secular world’s imagination, whilst the monastic tradition manifested the spiritual aspiration.

Of course, we may feel cynical about such traditions, knowing the brutality of which we, and those we believe should know better, are also capable. However, even this judgement arises from the same, more ‘noble’ motivations. Such ideals, whether or not they are attained in our lifetimes, can give direction to existence – even if we never finally ‘arrive’. The attraction is that inner strength is of great benefit to oneself, and to those with whom we come into contact. It is instinctually felt, and admired.