Martin Goodson

Low Impact Living

Exercises in Mindfulness

The idea that we should leave no traces of ourselves is implicit in Zen temples but, if we can consciously apply this to our daily lives, we will have a powerful tool for emptying out the heart.

©

© shutterstock

Back in the 1980s and 90s, I used to help administer the Buddhist Society’s annual Summer School. At that time, it consisted of two weeks: the first for those who were already in Buddhist practice in one of the three schools — Theravada, Tibetan, and Zen. This allowed participants to go deeper into the practice of their chosen tradition. The second week was for ‘newbies’ who wanted to dip their toe into the water and see what the different schools had to offer. This second week also attracted people who had previously been in practice, who may have left some years before, and wanted to reacquaint themselves with the Buddha Dharma once more.

I recall a number of people from the UK, Europe, and the USA coming along over time, and quite a few from the Zen schools. The Summer School was not a retreat, and so there was plenty of time to socialise; in fact, this was one of its great strengths, particularly as many lay Buddhists can feel they are on their own and don’t have other friends or family who are interested or to whom they can speak about these things.

Thus, I was surprised to hear from some ex-Zen practitioners that they had never heard of ‘daily life practice’. The Zen teacher at Summer School was Ven. Myokyo-ni (Daiyu Myokyo) and her talks consisted of little else but daily life practice. Hopefully, regular visitors to The Zen Gateway will be acquainted with this phrase too, as we make quite a bit of it here. Of course, everyone had heard of zazen and koans and interviews, but ‘daily life practice’ was, for many of these people returning from other Western groups, a brand-new concept. What is more, one or two had also been to Japan and said that there was no mention of it there in the Zen temples they had visited.

On occasion, Ven. Myokyo-ni talked about this difference. Some people thought that maybe she had made this up herself - that it was her own innovation and perhaps not ‘real Zen’. As it turned out, she was formalising something she found implicit in the culture around her and which fed directly into the training. Daily life practice seemed to consist of a number of strands. The first can be summed up by the injunction: ‘Give myself wholeheartedly into what at this moment is being done’. This was an exhortation to bring together body and mind-heart into the activity of the present moment, even if that activity was just sitting in a chair, but usually meaning any activity throughout the day. The next strand was called ‘form’. ‘Form’ governs posture (good deportment at all times), discipline, the structure of the day (often a timetable was used to create this structure), and good manners in dealing with others (involving restraint of impulses and passions, particularly in speech as well as in actions).

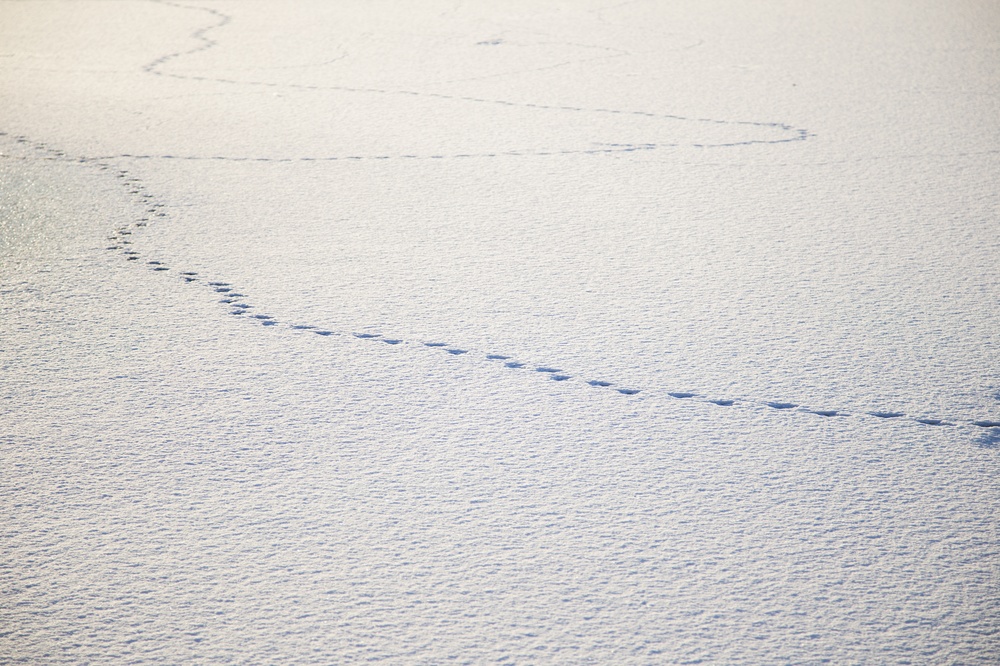

One general principle overarched this practice, which could be summed up as ‘low impact living’. It is the ability, through close awareness of the place we find ourselves in, to leave it as we find it. In practice, this can mean plumping up a cushion on an armchair after we vacate it, or putting a book we have been reading back on the shelf where we found it. It can mean washing up the cup, plate, or cutlery, drying it, and putting it back where it belongs after use. It can also mean not leaving things lying around generally — a habit of nest-building in places ‘I’ use frequently. In other words, in any place we find ourselves, not to stick out ‘like a sore thumb’.

In a temple or monastery, monks are judged on their ability to do just this. Hence the Japanese name for a monk is unsui - ‘cloud-water’. The implication is that the monk should move through the world as a cloud, or be like water, adapting to the shape of the situation with minimum impact. There is a verse in The Dhammapada along these lines too:

“As a bee gathers nectar from the flower and flies away without harming the flower’s beauty or its fragrance, just so the sage goes on his alms round in the village.” (Verse 49)

In this case it is about how the monk goes on alms round, collecting, but not greedily, for food. However, it is still a matter of low impact living.

Sokei-an also makes a similar point in his sermon The Shape of Meditation. He comments ruefully that in his time (New York City in the 1930s), guests would go to someone else’s home and within minutes put their feet up on the furniture, or lean back balancing their chairs precariously on two legs. This, he felt, lacked dignity and showed a lack of respect for how the hosts might like their furniture to be treated. This, too, is a failure of low-impact living.

Thus, when Myokyo-ni talked of daily life practice, she would admit that it was never talked about in Japan, and wasn’t during her own period of training in the 1960s. But, she would say, this is because good form, wholeheartedness, and natural consideration for others were taken for granted. Her analysis of the Western psyche and prevailing attitudes was that our emphasis on individualism has a downside: an overweening sense of entitlement to ‘my’ way of doing things, and a feeling that others should accommodate my whims and wishes, to the point that there is often a general lack of awareness of the surroundings. If I am called to ‘fit in’, this can produce a sense of anxiety - still based around me - that I might be corrected or scolded, which ‘I’ do not like at all!

Frequent visitors to the temple may be given simple housework to do. Dusting was a challenge, because all surfaces had to be cleaned, which meant moving items from shelves and mantelpieces, dusting, and then replacing them exactly as originally found. I cannot tell you how many times I thought I was paying attention to something, would remove it, and then could not recall exactly where it had been. The problem was that I was so preoccupied with ‘getting it right’ that the anxiety about being corrected caused doubt to arise and also interfered with seeing things clearly. More often than not, there was an aesthetic or logic to how things were placed, and looking at their placement afterwards ‘spoke’ and ‘told’ me where they belonged. It was the obsession with my anxiety that got in the way of seeing clearly.

Thus, Ven. Myokyo-ni created daily life practice as a skillful means to make visible what she had witnessed in those coming to the temple - what in Japan was taken for granted and thus never mentioned. The practice of “low impact living” de-emphasises the obsession with self and has a remarkable calming effect once undertaken. It only needs a few simple rules: just remember ‘cloud and water’, leave as few traces of ‘myself’ in going through the world as possible, and see for oneself how the attitude to the environment changes and how circumstances begin to ‘talk’ back to us - informing us of their needs: the plant that needs some water, the knife that asks to be put back in the drawer.

In one sutra it says, “All things are Buddha things”. This suggests taking the reverential attitude we cultivate in the Zendo into all aspects of our daily lives. See what that means in practice.